In 8 days I'll be done with my first year of graduate studies and will have a chance to write a bit more. I've been keeping notes all year on things to write about when I have more time, so I should have no shortage of material! In the meantime, two links to share: 1) Just in time for my summer working with the New York City Department of Health comes Epidemic City: The Politics of Public Health in New York. The Amazon / publisher's blurb:

The first permanent Board of Health in the United States was created in response to a cholera outbreak in New York City in 1866. By the mid-twentieth century, thanks to landmark achievements in vaccinations, medical data collection, and community health, the NYC Department of Health had become the nation's gold standard for public health. However, as the city's population grew in number and diversity, new epidemics emerged, and the department struggled to balance its efforts between the treatment of diseases such as AIDS, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, and West Nile Virus and the prevention of illness-causing factors like lead paint, heroin addiction, homelessness, smoking, and unhealthy foods. In Epidemic City, historian of public health James Colgrove chronicles the challenges faced by the health department in the four decades following New York City's mid-twentieth-century peak in public health provision.

This insightful volume draws on archival research and oral histories to examine how the provision of public health has adapted to the competing demands of diverse public needs, public perceptions, and political pressure.

Epidemic City delves beyond a simple narrative of the NYC Department of Health's decline and rebirth to analyze the perspectives and efforts of the people responsible for the city's public health from the 1960s to the present. The second half of the twentieth century brought new challenges, such as budget and staffing shortages, and new threats like bioterrorism. Faced with controversies such as needle exchange programs and AIDS reporting, the health department struggled to maintain a delicate balance between its primary focus on illness prevention and the need to ensure public and political support for its activities.

In the past decade, after the 9/11 attacks and bioterrorism scares partially diverted public health efforts from illness prevention to threat response, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Department of Health Commissioner Thomas Frieden were still able to work together to pass New York's Clean Indoor Air Act restricting smoking and significant regulations on trans-fats used by restaurants. Because of Bloomberg's willingness to exert his political clout, both laws passed despite opposition from business owners fearing reduced revenues and activist groups who decried the laws' infringement upon personal freedoms. This legislation preventative in nature much like the 1960s lead paint laws and the department's original sanitary code reflects a return to the 19th century roots of public health, when public health measures were often overtly paternalistic. The assertive laws conceived by Frieden and executed by Bloomberg demonstrate how far the mandate of public health can extend when backed by committed government officials.

Epidemic City provides a compelling historical analysis of the individuals and groups tasked with negotiating the fine line between public health and political considerations during the latter half of the twentieth century. By examining the department's successes and failures during the ambitious social programs of the 1960s, the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, the struggles with poverty and homelessness in the 1980s and 1990s, and in the post-9/11 era, Epidemic City shows how the NYC Department of Health has defined the role and scope of public health services, not only in New York, but for the entire nation.

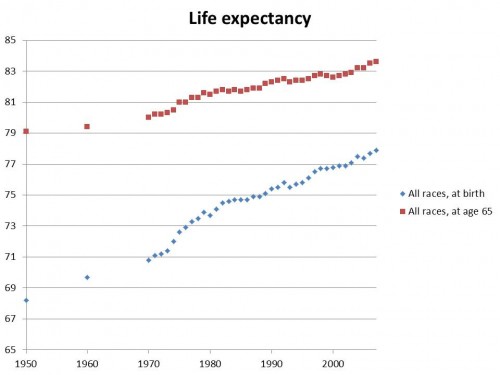

2) Aaron Carroll at the Incidental Economist writes about the subtleties of life expectancy. His main point is that infant mortality skews life expectancy figures so much that if you're talking about end-of-life expectations for adults who have already passed those (historically) most perilous times as a youngster, you really need to look at different data altogether.

The blue points on the graph below show life expectancy for all races in the US at birth, while the red line shows life expectancy amongst those who have reached the age of 65. Ie, if you're a 65-year-old who wants to know your chances of dying (on average!) in a certain period of time, it's best to consult a more complete life table rather than life expectancy at birth, because you've already dodged the bullet for 65 years.

(from the Incidental Economist)

(from the Incidental Economist)